|

|

|

|

|

Original Article

Farmers’ Need for Climate Services and Information for Agricultural Decision-Making in North-central Namibia

|

Cecil

Togarepi 1, Radi A. Tarawneh 2, Moammar Dayoub 3,

Rauna Nekongo 1,

Joel Muzanima 1,

Susanna Shivolo-Useb 1,

Khaled Al-Najjar 4* 1 Department of Animal

Production, Agribusiness and Economics, University of Namibia, Ogongo Campus,

Private Bag X5507, Oshakati, Namibia 2 Department of Economics, Faculty of

Agriculture, Jerash University, 26150 Jerash, Jordan 3 Department of Computing, Faculty of Technology,

Turku University, 20014 Turku, Finland 4 Department of Animal Wealth, Arab Center for the Studies of Arid Zones

and Dry Lands,2440 Damascus, Syria |

|

|

|

ABSTRACT |

||

|

This study aims to identify farmers' needs for climate and agricultural information, assess effectiveness of its delivery channels, and explore role of technology and mobile applications in improving access to climate services and enhancing agricultural adaptation. This is achieved through collection and analysis of quantitative and qualitative data from selected villages in Oshana and Omosati. Results show that majority of farmers in Oshana and Omosati are women (55.5%), and most have a secondary education or higher. Their ages range from young to middle-aged. They face significant challenges, including limited financing (51.7%), high production costs (29.1%), poor weather forecasting (75.5%), and prevalence of crop diseases (79.5%). They struggle to use mobile phones due to cost, weak network coverage, and a lack of training. Farmers need information on soil preparation (87%), fertilizers (81.5%), pesticide application (78.8%), resource management, and crop selection. They request comprehensive weather and climate data, with regional variations in some indicators. They primarily use radio (84.2%) and neighbours (67.8%) for information, while reliance on mobile phones (41.8%), computers (14.4%), and television (28.1%) is increasing. The study concludes that farmers need diverse climate services and information and communication technology tools, but they lack appropriate devices. They rely on soil and climate information to determine timing of land preparation, planting, fertilization, and pesticide management, and they often access this information via smartphones. It recommends educating farmers and providing them with timely and appropriate climate information, disseminating rainfall forecasts using accessible technologies, and supporting policies to enhance effectiveness of agricultural extension services. Keywords: Farm Technologies, Farmer

Requirements, Climate Data, Information. |

||

INTRODUCTION

Namibia is a

semi-arid country characterized by extreme climatic variability and high

environmental fragility, making it vulnerable to droughts, floods, and other

extreme weather events that directly impact agricultural productivity and rural

livelihoods Kaundjua

et al. (2012), Awala et

al. (2019), Amandaria

et al. (2025). These challenges are amplified in the

northern regions, which experience the highest rainfall and population density,

further straining agricultural ecosystems Ofoegbu

and New (2021a). Climate change contributes to increased

frequency and intensity of climate-related risks, reduced crop yields, and

deteriorating health and nutritional conditions, highlighting need to

strengthen farmers' resilience to these changes Montle

and Teweldemedhin (2014), Keja‑Kaereho and Tjizu (2019).

Reference studies

in arid environments show a growing interest in developing more sustainable

agricultural practices and enhancing agricultural sector's resilience to

climate change. Tarawneh

et al. (2025a) emphasize importance of bioeconomics in

promoting sustainability through renewable resources and international

cooperation. Abu Harb et al. (2024a) point to need for education and awareness to

support inclusive agricultural practices that are resilient to climate change.

Studies by Delfani

et al. (2024), Al-Lataifeh et

al. (2024), Dayoub

et al. (2024) and Tarawneh

et al. (2025b) highlight the growing role of smart

technologies in improving the environmental and economic performance of the

livestock sector. Research by Tarawneh

et al. (2022) and Tarawneh

and Al‑Najjar (2023) demonstrates the importance of agricultural

extension and financial support in promoting water resource sustainability and

empowering smallholder farmers. In context of food security, Abo Znemah et al. (2023) point to the factors influencing food income

and expenditure and their role in building resilience. Besides Al-Barakeh et al. (2024), who highlight the

potential of local livestock in achieving sustainable rural development. The

findings of Abu Harb et al. (2024b) support the adoption of technology as a

means to improve economic efficiency. This is in line with the growing research

trend that focuses on integrating technology, developing agricultural

knowledge, and enhancing resilience to climate change. This contributes to

shaping practical research directions that address current agricultural and

environmental challenges.

The problem

addressed by this study is the limited access of smallholder farmers in Namibia

to accurate and up-to-date climate information for making agricultural

decisions Cruz et al. (2021), Ofoegbu

and New (2021b). While farmers rely on traditional

adaptation mechanisms, the severity of current climate change and increasing

climate uncertainty exceeds the capacity of these mechanisms to respond

effectively Reid et al. (2008). Furthermore, weak agricultural extension

services, resource scarcity, the vast geographical area under cultivation, and

the emergence of new pests all contribute to reducing the effectiveness of

climate and agricultural information channels for farmers.

The importance of

this study lies in crucial role of climate information in improving

agricultural decision-making, particularly in fragile and semi-arid

environments. The literature emphasizes need to enhance access to climate

services through both formal and informal channels, as providing reliable and

timely climate information contributes to better agricultural risk management,

supports adaptation to changing conditions, and reduces the vulnerability of

rural livelihoods Vincent

et al. (2017), Tall et al. (2013), Tall et al. (2014), Tall et al. (2018), Hansen

et al. (2019). This role is further amplified by the increasing use of information

and communication technologies, which offer new opportunities for disseminating

and accessing climate data, thus supporting farmers' efforts to address

escalating climate risks Mapiye

et al. (2023).

The gap lies in

lack of systematic studies that focus on assessing actual needs of Namibian

farmers for climate services, identifying type of information required,

adequacy of existing delivery channels, and their receptiveness to modern

technological tools such as mobile applications Hewitt

et al. (2011), Brasseur

and Gallardo (2016). Furthermore, effectiveness of these tools

in addressing shortcomings of traditional extension systems and their potential

impact on promoting agricultural adaptation and improving decision-making

processes among smallholder farmers are not adequately examined.

Based on this

problem, the study aims to identify farmers' needs for climate and agricultural

information. It also seeks to support agricultural decision-making.

Furthermore, it assesses the effectiveness of formal and informal information

delivery channels and their ability to meet the needs of smallholder farmers.

In addition, the study explores the role of agricultural technology and mobile

applications in improving access to and dissemination of climate services. It

also estimates the demand for digital climate services and analyzes their

potential to enhance agricultural adaptation. Finally, it evaluates their role

in mitigating climate risks in semi-arid regions. Consequently, the study

contributes to a deeper scientific understanding of climate service development

in Namibia. This supports agricultural sustainability and enhances farmers'

capacity to respond effectively to increasing climate challenges.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

1)

Study

area

The study was

conducted in selected villages in two districts of north-central Namibia:

Oshana and Omusati. This region is home to the Owambo ethnic group, which

constitutes majority, representing 40% of Namibia's population Angula

and Kaundjua (2016). In Oshana district, the study was conducted

in three villages within the Ongwideva ward: Onamutai, Omatandu, and Okandji.

The population of the Onisi ward in Omusati district was estimated at 13,149,

distributed across three villages: Omaineni, Omakova, and Ibalila. The total

population of Omusati was 243,166, while the population of the wider Onisi ward

was approximately 34,065, comprising 7,717 households Namibia

Statistics Agency. (2014).

2)

Study

design and Sampling

A mixed research

design was used, collecting both quantitative and qualitative data using

open-ended and closed-ended questions to understand farmers' climate service

needs. A multi-stage sampling approach was employed to intentionally select the

Omosati and Oshana districts as case study sites. One constituency was then

selected from each district, and two villages from the Ongwedeva constituency,

along with the villages of Ibalila and Omaineni, were chosen. A simple random

sampling method was used to select approximately 20 households from each of the

selected villages. In the Ongwedeva constituency, 79 farmers were randomly

selected, with an equal number from each of the selected villages, for a total

of 146 respondents. The Cochrane formula was used to determine an appropriate

sample size that accurately represented the population. The sample size

estimation equation was applied at a confidence level of 90%, assuming

homogeneity of selected sites, using the formula (n₀ = (Z²pq)/e²), where

value of (Z=1.645) was adopted, and (p=q=0.5) was adopted due to lack of a

prior estimate of ratio.

3)

Data

collection and analysis

A survey was

conducted to determine farmers' need for climate, weather, and agricultural

information to make decisions regarding the production of major crops such as

millet, maize, cowpeas, and sorghum. A questionnaire with open-ended and

closed-ended questions was used to collect data. Data were gathered through a

pre-designed questionnaire administered via face-to-face interviews with

farmers. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize the data, employing

measures of variance, central tendency, and the chi-square test. The analysis

was performed using SPSS (2025).

RESULTS

Socioeconomic

characteristics of the respondents

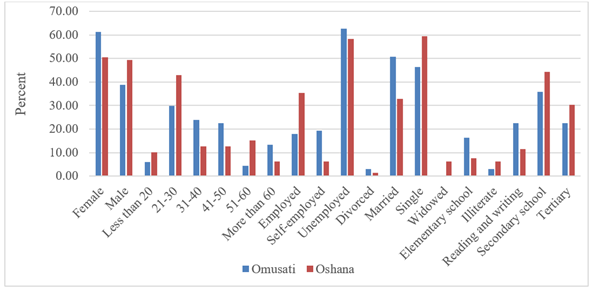

Figure 1 summarizes the demographic, social, and

economic characteristics of survey participants from selected villages in

Omosati and Oshana. The results indicate increased female participation in

agriculture. Most participants have at least a secondary education, and a

significant proportion hold university degrees. Age groups range from young to

elderly, with the majority being early to middle-aged. Marital status varies,

with a higher proportion of single participants. Employment status is

categorized as employed, self-employed, and unemployed, highlighting the

diversity of economic circumstances.

|

Figure 1 |

|

Figure 1 Distribution of Sociodemographic Characteristics

Across Regions |

Challenges faced in carrying out agricultural activities

Farmers report

facing a variety of challenges, most notably limited access to finance and

capital, particularly in Oshana Table 1. Other common difficulties, such as high

input costs, lack of weather forecasting information, crop diseases, and

inadequate agricultural extension services, affect farming activities across

different regions. The findings suggest that farmers face broadly similar

constraints regardless of their location.

Table 1

|

Table 1 Challenges Faced by

Respondents in Carrying Out Agricultural Activities |

|||||

|

Challenges

faced in agricultural activities |

Response |

Omusati

region |

Oshana

region |

Total |

Chi-Square

Value |

|

Obtain inputs (seeds,

fertilisers, pesticides, etc.) |

No |

12(17.4) |

12(14.6) |

24(15.9) |

0.21 |

|

Yes |

57(82.6) |

70(85.4) |

127(84.1) |

||

|

Weather forecasting to

start the planting season or timely activities |

No |

13(18.8) |

23(28.0) |

36(23.8) |

2.82 |

|

Yes |

55(79.7) |

59(72.0) |

114(75.5) |

||

|

High production costs |

No |

46(66.7) |

61(74.4) |

107(70.9) |

1.08 |

|

Yes |

23(33.3) |

21(25.6) |

44(29.1) |

||

|

Lack of market

information |

No |

49(71.0) |

50(61.0) |

99(65.6) |

3.23 |

|

Yes |

19(27.5) |

32(39.0) |

51(33.8) |

||

|

lack of finance and

capital (No access to credit) |

No |

40(58.0) |

32(39.0) |

72(47.7) |

7.03** |

|

Yes |

28(40.6) |

50(61.0) |

78(51.7) |

||

|

Crop diseases |

No |

12(17.4) |

16(19.5) |

28(18.5) |

0.62 |

|

Yes |

55(79.7) |

65(79.3) |

120(79.5) |

||

|

lack of extension

services |

No |

21(30.4) |

29(35.4) |

50(33.1) |

2.68 |

|

Yes |

46(66.7) |

53(64.6) |

99(65.6) |

||

|

Chi-square value with no

star means p>0.05, **p<0.01, and the percentages are placed in

parentheses. |

|||||

Challenges associated with ICT (mobile) usage in agricultural activities

Table 2 shows the main barriers faced by farmers in

the Omosati and Oshana regions when adopting mobile phone technology for

agricultural decision-making. The financial costs of phones and data are the

most significant obstacles, while electricity supply issues, weak communication

networks, and a lack of training are substantial limitations on technology use.

In contrast, barriers related to technical knowledge and language do not vary

significantly between regions, suggesting that the main constraints stem more from

economic and infrastructural factors than from farmers' knowledge and skills.

Table 2

|

Table 2 Barriers to Mobile

Technology Adoption in Agricultural Decision-Making: Insights from Namibian

Farmers |

|||||

|

Challenges

associated with mobile use in agricultural activities |

Characteristic |

Omusati

region |

Oshana

region |

Total |

Chi-Square

Value |

|

Price of smart mobile

phone |

No |

16(23.2) |

24(29.3) |

40(26.5) |

0.71 |

|

|

Yes |

53(76.8) |

58(70.7) |

111(73.5) |

|

|

Cost of data |

No |

28(40.6) |

42(51.2) |

70(73.5) |

1.71 |

|

|

Yes |

41(59.4) |

40(48.8) |

81(53.6) |

|

|

Electricity supply |

No |

21(30.4) |

54(65.9) |

75(49.7) |

18.80*** |

|

|

Yes |

48(69.6) |

28(34.1) |

76(50.3) |

|

|

Inadequate technical

knowhow |

No |

48(69.6) |

57(69.5) |

105(69.5) |

0.01 |

|

|

Yes |

21(30.4) |

25(30.5) |

46(30.5) |

|

|

High cost of acquiring

and maintenance |

No |

69(69.6) |

65(79.3) |

113(74.8) |

2.7 |

|

|

Yes |

20(29.0) |

17(20.7) |

37(24.5) |

|

|

Language barrier |

No |

56(81.2) |

68(82.9) |

124(82.1) |

1.05 |

|

|

Yes |

13(18.8) |

13(15.9) |

26(17.2) |

|

|

Telecommunications

network problems |

No |

29(42.0) |

52(63.4) |

81(53.6) |

8.42** |

|

|

Yes |

40(58.0) |

30(36.6) |

70(46.3) |

|

|

Lack of training on

mobile phone |

No |

65(58.0) |

65(79.3) |

130(86.1) |

7.13** |

|

|

Yes |

4(5.8) |

17(20.7) |

21(13.9) |

|

|

Prefer use of

radio/television broadcasting for agricultural information |

No |

58(84.1) |

58(70.7) |

116(76.8) |

3.74* |

|

|

Yes |

11(15.9) |

24(29.3) |

35(23.2) |

|

|

Other |

No |

66(95.7) |

82(100.0) |

148(98.0) |

3.64* |

|

Yes |

3(4.3) |

0(0.0) |

3(2.0) |

||

|

Chi-square value with no

star means p>0.05, *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, and the

percentage are placed in parentheses. |

|||||

Climate services information required by farmers to support agricultural decision-making

Although not

statistically significant, most participants sought information on soil

preparation timing, fertilizer application rates, and pesticide timing Table 3. The primary needs for climate services were

for resource allocation related to labor, finance, and pesticide application

timing. Farmers identified several reasons for requesting weather information,

including soil preparation, weed control, crop selection, irrigation

management, and resource allocation. Many farmers rely on manual methods and

local knowledge to assess soil moisture and sometimes consult their neighbors

for advice on fertilizer use. This information is crucial for cost management

and efficient irrigation, making soil moisture data vital for making daily

decisions in agricultural activities.

Table 3

|

Table 3 Types of Agricultural-Related

Information Needed by Farmers for Agricultural Decision-Making |

|||||

|

Variable |

Characteristic |

Omusati

region |

Oshana

region |

Total |

Chi-Square

Value |

|

Timing of preparation

for the soil |

Yes |

57(85.1) |

70(88.6) |

127(87.0) |

0.4 |

|

|

No |

10(14.9) |

9(11.4) |

19(13.0) |

|

|

Timing of weeding |

Yes |

37(55.2) |

36(45.6) |

73(50.0) |

1.35 |

|

|

No |

30(44.8) |

43(54.4) |

73(50.0) |

|

|

Choosing of crops/crop

variety (depend on season dry/wet) |

Yes |

42(62.7) |

51(64.6) |

93(63.7) |

0.06 |

|

|

No |

25(37.3) |

28(35.4) |

53(36.3) |

|

|

Irrigation management

in terms of timing of irrigation and quantity of water to be applied |

Yes |

24(35.8) |

22(27.8) |

46(31.5) |

1.07 |

|

|

No |

43(64.2) |

57(72.2) |

100(68.5) |

|

|

Resource use

allocation both labour and finances] |

Yes |

14(20.9) |

27(34.2) |

41(28.1) |

3.17* |

|

|

No |

53(79.1) |

52(65.8) |

105(71.9) |

|

|

Fertiliser application

the quantity and type of fertiliser as well as the timing of application of

fertilisers on crops |

Yes |

52(77.6) |

67(84.8) |

119(81.5) |

1.25 |

|

|

No |

15(22.4) |

12(15.2) |

27(18.5) |

|

|

Timing of pesticide

application |

Yes |

46(68.7) |

69(87.3) |

115(78.8) |

7.57*** |

|

No |

21(31.3) |

10(12.7) |

31(21.2) |

||

|

Chi-square value with no

star means p>0.05, *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, and the percentage are

placed in parentheses. |

|||||

Table 4 shows that farmers in the Omosati and Oshana

regions have a high demand for various types of climate information to support

agricultural decision-making. This includes weather forecasts, rainfall data,

temperature readings, and predictions related to climate change and flooding.

These findings highlight the importance of providing accurate and comprehensive

climate information to facilitate agricultural planning and climate-risk-based

decision-making.

Table 4

|

Table 4 Types of

Climate-Related Information Demanded by Farmers to Support Agricultural

Decision-Making |

|||||

|

Variable |

Characteristic |

Omusati

region |

Oshana

region |

Total |

Chi-Square

Value |

|

Weather forecasting |

No |

2(3.0) |

8(10.1) |

10(6.8) |

2.89* |

|

|

Yes |

65(97.0) |

71(89.9) |

136(93.2) |

|

|

Soil temperature at

different depths |

No |

18(26.9) |

17(21.5) |

35(24.0) |

0.56 |

|

|

Yes |

49(73.1) |

62(78.5) |

111(76.0) |

|

|

Rainfall |

No |

9(13.4 |

4(5.1) |

13(8.9) |

3.13* |

|

|

Yes |

58(86.6) |

75(94.9) |

133(91.1) |

|

|

Climate change

projections |

No |

2(3.0) |

2(2.5) |

4(2.7) |

0.03 |

|

|

Yes |

65(97.0) |

77(97.5) |

142(97.3) |

|

|

Flood projections |

No |

3(4.5) |

1(1.3) |

4(2.7) |

1.4 |

|

|

Yes |

64(95.5) |

78(98.7) |

142(97.3) |

|

|

Temperature

projections |

No |

2(3.0) |

1(1.3) |

3(2.1) |

0.53 |

|

Yes |

65(97.0) |

78(98.7) |

143(97.9) |

||

|

Chi-square value with no

star means p>0.05, *p<0.05, and the percentage are placed in

parentheses. |

|||||

Figure 2 illustrates regional differences in farmers'

needs for specific weather information. Therefore, general weather forecasts

are recommended. Statistically significant differences were found between

Omosati and Oshana regions regarding the importance of temperature, soil

temperature, radiation, humidity, evaporation, and precipitation. Other weather

parameters, including different types of forecasts and projections, did not

show any statistically significant regional differences.

|

Figure 2 |

|

|

|

Figure 2 Comparison of Weather-Related Information

Needs for Agricultural Decision-Making in Omusati and Oshana Regions, Namibia |

Figure 3 illustrates why farmers need weather

information, considering the global importance of soil preparation. Resource

allocation and the timing of pesticide application showed significant regional

variations. Other factors, such as sowing and irrigation, also vary, but not as

drastically.

|

Figure 3 |

|

|

|

Figure 3 Reasons Farmers Need Weather Related

Information |

The results in Figure 4 show that the majority of respondents

received their weather and climate information via radio, totaling 84.2%. An

additional 67.8% of participants reported receiving weather information from

their neighbors. Only a small percentage received information from extension

workers.

|

Figure 4 |

|

|

|

Figure 4 Farmers’ Main Sources of Climate Related

Information |

Radio broadcasting

remains a central channel for agricultural information in Namibia, as shown in Figure 4 However, this dominance faces clear

challenges, as illustrated in Figure 5 The weak telecommunications infrastructure

highlights the need for effective alternatives, and the accuracy of information

gathered from farmers raises several concerns. Consequently, participants are

now turning to mobile phones and the internet, with a significant increase in

computer usage, indicating a strategic shift towards more diverse information

sources.

|

Figure 5 |

|

|

|

Figure 5 Access to Media and ICT Tools for

Agricultural Information |

DISCUSSIONS

Demographic,

social and economic characteristics

The demographic

and socioeconomic characteristics of the respondents revealed gender dynamics,

education levels, and employment status in Omusati and Oshana. Women

outnumbered men, highlighting their central role in agriculture and rural

livelihoods. This is consistent with broader findings on women's contributions

to agriculture and food production under climate variability. Education

influences access to agricultural and climate information, with most

respondents having at least a secondary education. Employment opportunities

varied, with a significant proportion unemployed. Gumucio

et al. (2020) underscore the roles of gender in accessing

resources and making climate-related decisions, reinforcing the need for

gender-sensitive climate services. Vo et al. (2023) emphasized the importance of considering

sociodemographic differences to avoid bias, while Fel et al. (2022) highlighted the links between demographics, dietary patterns, and

social support needs.

Production challenges and need for institutional support

Farmers in both

regions face significant challenges, with limited access to finance being the

most pressing, particularly in Oshana. High input costs, unreliable weather

forecasting, crop diseases, and inadequate agricultural extension services also

hinder productivity. These widespread problems highlight the need for improved

financial support, climate information, and agricultural extension services. Nyarko

and Kozári (2021) emphasize the importance of incentives, ICT

integration, and stronger extension services for achieving agricultural

sustainability Rahman

and Huq (2023), Anteneh

and Melak (2024).

Obstacles to adoption of information and communication technologies

The adoption of

information and communication technologies (ICTs) in the agricultural sector

faces significant regional challenges. These include weak infrastructure, low

mobile phone literacy, and continued preference for traditional media such as

radio. The high cost of smartphones and data services is a major barrier to

adoption, highlighting the need for policies that promote affordability. Krell et

al. (2021) indicate that mobile services have promising

potential to support agricultural development, but their use remains limited

due to high costs and weak farmers' networks. Quandt

et al. (2020) link mobile phone use to improved maize

productivity in Tanzania. Kabirigi

et al. (2023) demonstrate that usage patterns vary

according to farm type, education level, and age group.

Farmers' priorities and information gaps

Farmers prioritize

practical climate services information. They focus on soil preparation,

fertilizer use, and pest control. However, resource management and the timing

of pesticide application have a greater impact on climate services utilization.

Farmers rely on manual soil moisture assessment and consult neighbors for

fertilizer advice. This reflects gaps in access to reliable scientific data and

local guidance. Sutanto

et al. (2022) emphasize the role of soil moisture in

improving irrigation and weed control at a reasonable cost. Zhai et al. (2020) highlight the challenges in agricultural

decision support systems. Borrero and Mariscal (2022) focus on the importance

of governance and collaboration in digital platforms. Ara et al. (2021) advocate for participatory design to promote

the adoption of decision support services.

Demand for and access to climate information

Over 90% of

farmers seek climate-related information. This reflects their concern about

increasing droughts, rising extreme temperatures, and erratic rainfall patterns

in Namibia Spear

and Chappel (2018), Keja‑Kaereho and Tjizu (2019); Van and Biradar (2021). Despite the availability of data, several

barriers hinder its use. These include format, language, and accessibility.

This aligns with Ncoyini

et al. (2022), who emphasize the importance of tailoring

climate information to the needs of end users. Myeni et

al. (2024) highlight the need for accessible climate

services to enhance resilience. Ritu and Kaur

(2024) underscore the role of attitudes, benefits, and support systems

in adoption. Hasan

and Kumar (2019) and Kumar et

al. (2020) advocate for participatory approaches to

improve decision-making.

Regional variations and importance of dedicated data

Regional

variations in weather information reflect local agricultural practices. General

forecasts are evaluated on a global scale. However, temperature, soil

temperature, radiation, humidity, evaporation, and rainfall show clear regional

differences between Omosati and Ochana. This finding highlights the need for

climate services tailored to each region. Yegbemey

et al. (2023) and Yegbemey and Egah (2020) confirm that

appropriate weather data improves agricultural decisions. Mabhaudhi

et al. (2025) also emphasize the role of such data in

supporting climate-smart agriculture. Yegbemey

et al. (2023) report that SMS-based rainfall forecasting

in Benin increases productivity and reduces costs.

Demand drivers and influence of local context

The reasons

farmers seek weather information reflect both global and regional needs. Soil

preparation is critical globally, but resource allocation and the timing of

pesticide application vary by region and are influenced by local practices and

pest pressures. Differences in the importance of sowing and irrigation were not

statistically significant. Kumar et

al. (2021) noted that trust and context influence the

use of hydro-climatic information. Ncoyini

et al. (2022) attribute weak participation to training

gaps and language barriers. Foguesatto

et al. (2020) highlight that extreme weather events,

rather than data, shape farmers' perceptions of climate.

Communication channels between traditional and digital

Farmers primarily

rely on traditional channels for weather information. Radio is the main source,

followed by information sharing among neighbors. Formal agricultural extension

services play a limited role. This situation highlights a clear gap in the dissemination

of official information. Popoola

et al. (2020) emphasize the effectiveness of media

compared to extension services. Paparrizos

et al. (2023) highlight the role of farmer support

applications in building trust through shared climate services. Rust et al. (2022) emphasize the increasing influence of social

media and farmer networks in knowledge sharing.

Infrastructure and E-Readiness

Limited ICT

infrastructure hinders farmers' access to agricultural information. Radio

dominates communication channels, while newer technologies are gaining

popularity. Weak networks limit mobile phone usage, despite the increasing

reliance on computers and mobile devices. Balancing traditional and digital

channels remains crucial for effective information dissemination. Mansour

et al. (2024) notes that ICT provides market and technical

knowledge, although barriers related to literacy, costs, and awareness persist.

Assessing e-readiness using frameworks such as the Network Readiness Index can

promote digital integration and support agricultural sustainability.

The gap in ownership and use of technological tools

Access to

information and communication technologies (ICTs) is crucial for climate

adaptation, yet many farmers face barriers, such as limited access to mobile

phones, computers, and radios Vaughan

and Dessai (2014), Vincent

et al. (2017). These limitations affect farmers' ability

to access climate services. The study indicates that farmers with limited

resources have limited access to media, although some use smartphones to access

climate information. Of the 133 participants, 91% use mobile phones, but only

60% own them, highlighting a mobile phone ownership gap Asa and Uwem (2017). The researchers demonstrate that mobile

phones are effective in providing agricultural information in Nigeria,

suggesting the need to strengthen mobile extension services Duncombe

et al. (2016).

Implications for policies, research, and practices

The findings

indicate the need for policy support in disseminating climate, weather, and

agricultural information, along with appropriate digital support to bridge the

digital divide. This access accelerates decision-making and reduces the time

and cost required for sound agricultural decisions. Research is needed to

determine farmers' willingness to accept and pay for climate services, and the

factors influencing this willingness. It is needed to identify barriers to

providing climate services to farmers, enabling the design of effective policy

interventions. In practice, farmers should be clear about their needs, advocate

for them, and organize themselves to reduce transaction costs and increase

their bargaining power. The exchange of climate and agricultural information

must be tailored to farmers' needs. It must also be easily understandable,

interpretable, and usable for agricultural decision-making and planning. This

approach strengthens farmers' resilience and empowers them to make informed and

timely decisions.

CONCLUSIONS and RECOMMENDATIONS

It can be

concluded that farmers need a variety of climate services, including

information and communication technology (ICT) tools and diverse climate

information, and the results show that they are aware of the existence of these

services. However, they lack access to appropriate ICT tools, such as

televisions and computers. Therefore, the government should develop programs to

provide ICT facilities to farmers to enhance food security in the country.

Farmers place

great importance on soil moisture and climate information to help them make

decisions related to their farms. This information can be used to determine the

timing of land preparation, seed planting, fertilizer application, weeding, and

pesticide application. Farmers can easily access climate information through

devices such as smartphones. Extension services can also organize field days,

distribute brochures, and make information available through physical or

digital methods.

Some farmers have

a limited understanding of weather information or are not well aware of it.

Therefore, agricultural extension services recommend educating farmers about

weather information and climate services. The study also recommends that

extension staff provide farmers with appropriate and timely climate knowledge

and information to use in reducing climate-related losses and maximizing

benefits, such as protecting lives and livelihoods.

Farmers want

access to short- and long-term rainfall forecasts. Therefore, disseminating

this information requires the use of appropriate and accessible technologies

that enable people to obtain climate information and agricultural services.

This must be coupled with appropriate policy interventions and strategies to

enhance the effectiveness of agricultural extension services.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The researchers

extend their sincere thanks to University of Namibia, University of Jerash,

University of Turku, and General Commission for Agricultural Scientific

Research in Syria for their scientific and technical support. They express

their gratitude to the farmers and participants in north-central Namibia for

their cooperation in providing study data.

REFERENCES

Abo Znemah, S., Tarawneh, R., Shnaigat, S., and Al‑Najjar, K. (2023). Estimating some Indicators of Food Security for Rural Households. Asian Journal of Agriculture and Food Sciences, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.24203/ajafs.v11i2.7171

Abu Harb, S., Dayoub, M., and Al‑Najjar, K. (2024b). The Impact of Agricultural Extension Program Effectiveness on Sustainable Farming: A Survey Article. International Journal of Agricultural Technology, 20(2), 477–492.

Abu Harb, S., Tarawneh, R. A., Abu Hantash, K. L. A., Altarawneh, M., Al‑Najjar, K., and Daxue Xuebao, H. (2024a). Empowering Rural Youth Through Sustainable Innovation, Entrepreneurship and Peer Learning in Agriculture. Journal of Hunan University Natural Sciences.

Al‑Barakeh, F., Khashroum, A. O., Tarawneh, R. A., Al‑Lataifeh, F. A., Al‑Yacoub, A. N., Dayoub, M., and Al‑Najjar, K. (2024). Sustainable Sheep and Goat Farming in Arid Regions of Jordan. Ruminants, 4(2), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants4020017

Al‑Lataifeh, F. A., Tarawneh, R. A., Dayoub, M., Sutinen, E., and Al‑Najjar, K. (2024). Smart Technologies for Livestock Sustainability and Overcoming Challenges: A Review. Ebraheem S. Al‑Taha’at. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.13744058

Amandaria, R., Darma, R., Zain, M. M., Fudjaja, L., Wahda, M. A., Kamarulzaman, N. H., Bakheet Ali, H., and Akzar, R. (2025). Sustainable resilience in Flood‑Prone Rice Farming: Adaptive Strategies and Risk‑Sharing Around Tempe Lake, Indonesia. Sustainability, 17(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/su17062456

Angula, M. N., and Kaundjua, M. B. (2016). The Changing Climate and Human Vulnerability in North‑Central Namibia. Jamba: Journal of Disaster Risk Studies, 8(2), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.4102/jamba.v8i2.200

Anteneh, A., and Melak, A. (2024). Ict‑Based Agricultural Extension and Advisory Service in Ethiopia: A Review. Cogent Food & Agriculture, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311932.2024.2391121

Ara, I., Turner, L., Harrison, M. T., Monjardino, M., deVoil, P., and Rodriguez, D. (2021). Application, Adoption and Opportunities for Improving Decision Support Systems in Irrigated Agriculture: A Review. Agricultural Water Management, 257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2021.107161

Asa, U. A., and Uwem, C. A. (2017). Utilization of Mobile Phones for Agricultural Purposes by Farmers in Itu Area, Nigeria. European Scientific Journal, 13(19), 395. https://doi.org/10.19044/esj.2017.v13n19p395

Awala, S. K., Hove, K., Wanga, M. A., Valombola, J. S., and Mwandemele, O. D. (2019). Rainfall Trend and Variability in Semi‑Arid Northern Namibia: Implications for Smallholder Agricultural Production. WIJAS, 1.

Borrero, J. D., and Mariscal, J. (2022). A Case Study of a Digital Data Platform for the Agricultural Sector: A Valuable Decision Support System for small farmers. Agriculture, 12(6). https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture12060767

Brasseur, G. P., and Gallardo, L. (2016). Climate Services: Lessons Learned and Future Prospects. Earth’s Future, 4(3), 79–89. https://doi.org/10.1002/2015EF000338

Cruz, G., Gravina, V., Baethgen, W. E., and Taddei, R. (2021). A Typology of Climate Information users for Adaptation to Agricultural Droughts in Uruguay. Climate Services, 22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2021.100214

Dayoub, M., Shnaigat, S., Tarawneh, R. A., Al‑Yacoub, A. N., Al‑Barakeh, F., and Al‑Najjar, K. (2024). Enhancing Animal Production Through Smart Agriculture: Possibilities, Hurdles, Resolutions, and Advantages. Ruminants, 4(1), 22–46. https://doi.org/10.3390/ruminants4010003

Delfani, P., Thuraga, V., Banerjee, B., and Chawade, A. (2024). Integrative Approaches in Modern Agriculture: IoT, ML and AI for Disease Forecasting Amidst Climate Change. Precision Agriculture. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11119-024-10164-7

Duncombe, R. (2016). Mobile Phones for Agricultural and Rural Development: A Literature Review and Suggestions for Future Research. European Journal of Development Research, 28(2), 213–235. https://doi.org/10.1057/EJDR.2014.60

Fel, S., Jurek, K., and Lenart‑Kłoś, K. (2022). Relationship between Socio‑Demographic Factors and Post‑Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Cross‑Sectional Study Among Civilian Participants in Hostilities in Ukraine. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052720

Foguesatto, C. R., Artuzo, F. D., Talamini, E., and Machado, J. A. D. (2020). Understanding the Divergences Between Farmers’ Perception and Meteorological Records Regarding Climate Change: A Review. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 22(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-018-0193-0

Gumucio, T., Hansen, J., Huyer, S., and van Huysen, T. (2020). Gender‑responsive Rural Climate Services: A Review of the Literature. Climate and Development, 12(3), 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2019.1613216

Hansen, J. W., Vaughan, C., Kagabo, D. M., Dinku, T., Carr, E. R., Körner, J., and Zougmoré, R. B. (2019). Climate Services Can Support African Farmers’ Context‑Specific Adaptation Needs at Scale. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 3, 21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2019.00021

Hasan, M. K., and Kumar, L. (2019). Comparison between Meteorological Data and Farmer Perceptions of Climate Change and Vulnerability in Relation to Adaptation. Journal of Environmental Management, 237, 54–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2019.02.028

Hewitt, C., Mason, S., and Walland, D. (2011). The Global Framework for Climate Services. http://go.nature.com/OrPV1W

IBM Corp. (2025). IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 25). IBM Corporation. https://www.ibm.com/products/spss-statistics

Kabirigi, M., Sekabira, H., Sun, Z., and Hermans, F. (2023). The use of Mobile Phones and the Heterogeneity of Banana Farmers in Rwanda. Environment, Development and Sustainability, 25(6), 5315–5335. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10668-022-02268-9

Kaundjua, M. B., Angula, M. N., and Angombe, S. T. (2012). Community Perceptions of Climate Change and Variability Impacts in Oshana and Ohangwena Regions.

Keja‑Kaereho, C., and Tjizu, B. R. (2019). Climate Change and Global Warming in Namibia: Environmental Disasters vs. Human Life and the Economy. Management and Economics Research Journal, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.18639/MERJ.2019.836535

Krell, N. T., Giroux, S. A., Guido, Z., Hannah, C., Lopus, S. E., Caylor, K. K., and Evans, T. P. (2021). Smallholder Farmers’ use of Mobile Phone Services in Central Kenya. Climate and Development, 13(3), 215–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2020.1748847

Kumar, U., Werners, S. E., Paparrizos, S., Datta, D. K., and Ludwig, F. (2021). Co‑Producing Climate Information Services with Smallholder Farmers in the Lower Bengal Delta: How Forecast Visualization and Communication Support Farmers’ Decision‑making. Climate Risk Management, 33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.crm.2021.100346

Kumar, U., Werners, S., Roy, S., Ashraf, S., Hoang, L. P., Datta, D. K., and Ludwig, F. (2020). Role of Information in Farmers’ Response to Weather and Water‑Related Stresses in the Lower Bengal Delta, Bangladesh. Sustainability, 12(16). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12166598

Mabhaudhi, T., Dirwai, T. L., Taguta, C., Senzanje, A., Abera, W., Govid, A., Dossou‑Yovo, E. R., Aynekulu, E., and Petrova Chimonyo, V. G. (2025). Linking Weather and Climate Information Services (WCIS) to Climate‑smart Agriculture (CSA) Practices. Climate Services, 37, 100529. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2024.100529

Mansour, E. (2024). Information and Communication Technologies’ (ICTs) Use Among Farmers in Qena Governorate of Upper Egypt. Library Hi Tech, 42(4), 1266–1285. https://doi.org/10.1108/LHT-11-2021-0422/FULL/XML

Mapiye, O., Makombe, G., Molotsi, A., Dzama, K., and Mapiye, C. (2023). Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs): The Potential for Enhancing the Dissemination of Agricultural Information and Services to Smallholder Farmers in Sub‑Saharan Africa. Information Development, 39(3), 638–658. https://doi.org/10.1177/02666669211064847

Montle, B. P., and Teweldemedhin, M. Y. (2014). Assessment of Farmers’ Perceptions and the Economic Impact of Climate Change in Namibia: Case Study on Small‑Scale Irrigation Farmers (SSIFs) of Ndonga Linena Irrigation Project. Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 6(11), 443–454. https://doi.org/10.5897/jdae2014.0596

Myeni, L., Mahleba, N., Mazibuko, S., Moeletsi, M. E., Ayisi, K., and Tsubo, M. (2024). Accessibility and Utilization of Climate Information Services for Decision‑Making in Smallholder Farming: Insights from Limpopo Province, South Africa. Environmental Development, 51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envdev.2024.101020

Namibia Statistics Agency. (2014). Population and Housing Census: Kharas Region Profile. https://nsa.org.na/document-category/

Ncoyini, Z., Savage, M. J., and Strydom, S. (2022). Limited Access and use of Climate Information by Small‑Scale Sugarcane Farmers in South Africa: A Case Study. Climate Services, 26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2022.100285

Nyarko, D. A., and Kozári, J. (2021). Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) Usage Among Agricultural Extension Officers and its Impact on Extension Delivery in Ghana. Journal of the Saudi Society of Agricultural Sciences, 20(3), 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jssas.2021.01.002

Ofoegbu, C., and New, M. (2021a). Collaboration Relations in Climate Information Production and Dissemination to Subsistence Farmers in Namibia. Environmental Management, 67(1), 133–145. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-020-01383-5

Ofoegbu, C., and New, M. (2021b). The Role of Farmers and Organizational Networks in Climate Information Communication: The Case of Ghana. International Journal of Climate Change Strategies and Management, 13(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCCSM-04-2020-0030

Paparrizos, S., Dogbey, R. K., Sutanto, S. J., Gbangou, T., Kranjac‑Berisavljevic, G., Gandaa, B. Z., Ludwig, F., and van Slobbe, E. (2023). Hydro‑Climate Information Services for Smallholder Farmers: FarmerSupport app Principles, Implementation, and Evaluation. Climate Services, 30, 100387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2023.100387

Popoola, O. O., Yusuf, S. F. G., and Monde, N. (2020). Information Sources and Constraints to Climate Change Adaptation Amongst Smallholder Farmers in Amathole District Municipality, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability, 12(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/su12145846

Quandt, A., Salerno, J. D., Neff, J. C., Baird, T. D., Herrick, J. E., McCabe, J. T., Xu, E., and Hartter, J. (2020). Mobile Phone Use is Associated with Higher Smallholder Agricultural Productivity in Tanzania, East Africa. PLoS ONE, 15(8). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237337

Rahman, M. M., and Huq, H. (2023). Implications of ICT for the Livelihoods Of Women Farmers: A Study in the Teesta River Basin, Bangladesh. Sustainability, 15(19). https://doi.org/10.3390/su151914432

Reid, H., Sahlén, L., Stage, J., and Macgregor, J. (2008). Climate Change Impacts on Namibia’s Natural Resources and Economy. Climate Policy, 8(5), 452–466. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2008.9685709

Ritu, R. K., and Kaur, A. (2024). Unveiling Indian Farmers’ Adoption of Climate Information Services for Informed Decision‑Making: A Path to Agricultural Resilience. Climate and Development. https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2024.2409774

Rust, N. A., Stankovics, P., Jarvis, R. M., Morris‑Trainor, Z., de Vries, J. R., Ingram, J., Mills, J., Glikman, J. A., Parkinson, J., Toth, Z., Hansda, R., McMorran, R., Glass, J., and Reed, M. S. (2022). Have farmers had enough of experts? *Environmental Management, 69(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01546-y

Spear, D., and Chappel, A. (2018). Livelihoods on the Edge Without a Safety net: The Case of Smallholder Crop Farming in North‑Central Namibia. Land, 7(3). https://doi.org/10.3390/land7030079

Sutanto, S. J., Paparrizos, S., Kranjac‑Berisavljevic, G., Jamaldeen, B. M., Issahaku, A. K., Gandaa, B. Z., Supit, I., and van Slobbe, E. (2022). The Role of Soil Moisture Information in Developing Robust Climate Services for Smallholder Farmers: Evidence from Ghana. Agronomy, 12(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/agronomy12020541

Tall, A., Coulibaly, J. Y., and Dayoub, M. (2018). Do Climate Services Make a Difference? A Review of Evaluation Methodologies and Practices to Assess the value of Climate Information Services for Farmers: Implications for Africa. Climate Services, 11, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2018.06.001

Tall, A., Hansen, J., Jay, A., Campbell, B., Kinyangi, J., Aggarwal, P. K., and Zougmoré, R. (2014). Scaling up Climate Services for Farmers: Mission Possible.

Tall, A., Jay, A., and Hansen, J. (2013). Scaling Up Climate Services for Farmers in Africa and South Asia: Workshop Report, December 10–12, 2012, Saly, Senegal.

Tarawneh, R. A., Abu Harb, S., Dayoub, M., and Al‑Najjar, K. (2025a). Leveraging the Bio‑Economy to Drive Sustainable Development: A Comprehensive Review. International Journal of Agricultural Technology, 21(1), 327–338.

Tarawneh, R. A., Al‑Absi, K., Tarawneh, M. S., Al‑Mufti, M. O., and Al‑Najjar, K. (2025b). Policy and Demographic Determinants Influencing Agricultural Technology Adoption in Jordan. International Journal of Applied Science and Engineering Review, 6(6), 1–19. https://ijaser.org

Tarawneh, R. A., and Al‑Najjar, K. (2023). Assessing the Impacts of Agricultural Loans on Agricultural Sustainability in Jordan. IOSR Journal of Economics and Finance, 14, 49–56. https://doi.org/10.9790/5933-1406014956

Tarawneh, R., Tarawneh, M. S., and Al‑Najjar, K. A. (2022). Agricultural Policies Among Advisory and Cooperative Indicators in Jordan. International Journal of Research – Granthaalayah, 10*(2), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.29121/granthaalayah.v10.i2.2022.4489

Van Ginkel, M., and Biradar, C. (2021). Drought Early Warning in Agri‑Food Systems. Climate, 9(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/cli9090134

Vaughan, C., and Dessai, S. (2014). Climate Services for Society: Origins, Institutional Arrangements, and Design Elements for an Evaluation Framework. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Climate Change, 5(5), 587–603. https://doi.org/10.1002/wcc.290

Vincent, K., Dougill, A. J., Dixon, J. L., Stringer, L. C., and Cull, T. (2017). Identifying Climate Services Needs for National Planning: Insights from Malawi. Climate Policy, 17(2), 189–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2015.1075374

Vo, C. Q., Samuelsen, P. J., Sommerseth, H. L., Wisløff, T., Wilsgaard, T., and Eggen, A. E. (2023). Comparing the Sociodemographic Characteristics of Participants and Non‑Participants in the Population‑Based Tromsø Study. BMC Public Health, 23(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-023-15928-w

Yegbemey, R. N., Bensch, G., and Vance, C. (2023). Weather Information and Agricultural Outcomes: Evidence from a Pilot Field Experiment in Benin. World Development, 167, 106178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106178

Yegbemey, R. N., and Egah, J. (2021). Reaching out to Smallholder Farmers in Developing Countries with Climate Services: A Literature Review of Current Information Delivery Channels. Climate Services, 23, 100253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cliser.2021.100253

Zhai, Z., Martínez, J. F., Beltran, V., and Martínez, N. L. (2020). Decision Support Systems for Agriculture 4.0: Survey and Challenges. Computers and Electronics in Agriculture, 170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2020.105256

|

|

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

This work is licensed under a: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

© JISSI 2026. All Rights Reserved.